It started with a visit—not to a museum, but to family.

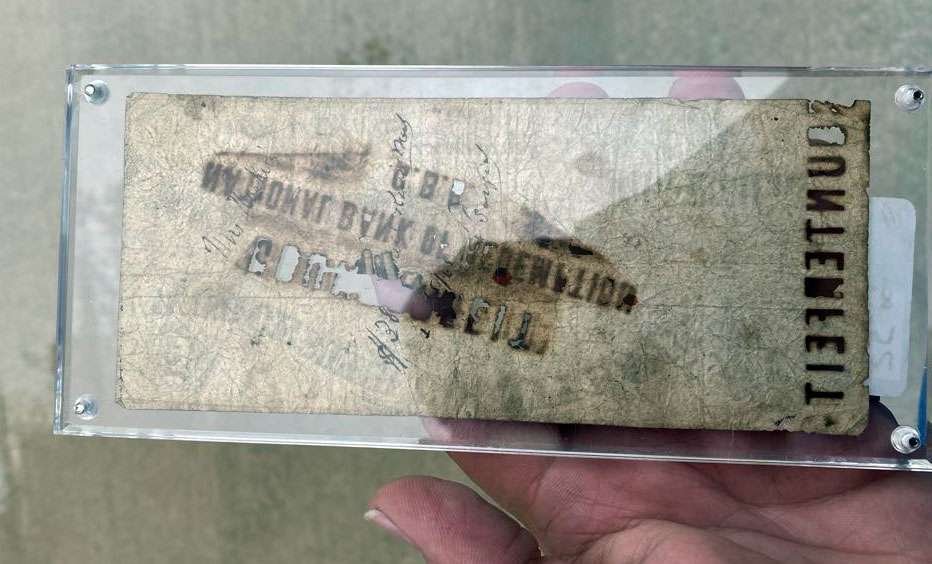

A few years ago, Mr. and Mrs. Ferrelli, who had recently moved to Blackstone, traveled to Wisconsin to visit Mr. Ferrelli’s father. One afternoon, while browsing Memories Antique Mall, they spotted something curious: a scorched $5 bill from the 1800s.

What caught their attention wasn’t just the age—it was the word Blackstone printed boldly on the note. It was a surprise link to Blackstone’s old currency history, found far from home.

A deep, circular burn punched through its center, with the word “COUNTERFEIT” branded across it. Around the blackened hole were the ghostly remnants of two other inscriptions: “National Bank of Redemption” and “C.B.”, followed by a final letter burned so thoroughly it’s unreadable.

They didn’t know exactly what they had found—but they knew it had a story. And they brought it back with them, unknowingly returning it to the very town where it began.

From Monument Square to Museum Glass

If the bill looked local, that’s because it was.

As shared by the Blackstone Historical Commission in the July edition of the Blackstone Enlightener, the note was originally issued by the Worcester County Savings Bank of Blackstone. The bank, founded by local mill owner Welcome Farnum, once operated out of the brick block on Monument Square.

In the 1800s, small-town banks like this issued their own paper currency—each note a promise of value, backed by trust in the bank that printed it.

But this decentralized system had a major flaw: counterfeiting flourished.

With over 1,600 state-chartered banks in the United States producing their own unique notes during the so-called Free Banking Era (1837–1863), it was nearly impossible to verify what was real. There were no universal designs, no central verification system, and no standard security features. Historians estimate that up to one-third of all bills in circulation were counterfeit at the time.

To combat this chaos, merchants relied on printed guides—like Thompson’s Bank Note Reporter—to identify suspect bills. But even these could lag behind the creativity of counterfeiters. Some forged notes copied real banks like the Worcester County Savings Bank of Blackstone. Others invented fictional institutions with official-sounding names and ornate engravings.

The Ferrellis’ $5 note was one of those flagged. It was physically branded “COUNTERFEIT”, a widespread 19th-century tactic to prevent re-circulation. It also bears another intriguing mark: “National Bank of Redemption.” While not the name of a formal federal agency, similar phrasing appears on multiple notes from the period, likely tied to efforts by financial clearinghouses or bank agents tasked with withdrawing unfit or fraudulent currency as the country transitioned toward a centralized system.

Notes from the Worcester County Savings Bank of Blackstone aren’t just old—they’re rare. Several spurious versions, also marked “non-genuine,” appear in historical auctions, suggesting Blackstone’s early economy was far from immune to fraud. What’s most remarkable is how far this one traveled. Somehow, this scorched slip of paper made it from a bank near Monument Square in Blackstone, through the hands of merchants or travelers, and all the way to a Wisconsin antique store—only to be picked up by a couple who had just planted new roots in the very town printed on its face.

A Piece of History Comes Home

When the Ferrellis visited the Blackstone Museum and spoke with members of the Blackstone Historical Commission, they shared the story of their antique discovery. Rather than keeping it tucked away at home, they chose to loan it to the museum, believing it belonged where it could be shared and appreciated.

Today, that scorched $5 bill is on public exhibit, displayed alongside other local banknotes and historical artifacts. It stands as a quiet but powerful reminder of the risks, creativity, and everyday challenges of early American finance—reflected even in small towns like Blackstone.

It reminds us that real history often travels in tiny, fragile forms—and sometimes through unexpected places.

Got Something Old with a Story?

The Blackstone Museum welcomes both donations and loans of historical items. Whether it’s a receipt, newspaper clipping, letter, tool, uniform, or even a mystery like the Ferrellis’ note—your attic or bookshelf might hold something with deeper meaning.

The Ferrellis loved finding a piece of the past. But they didn’t want to be the only ones staring at it. Now, it’s part of something bigger—a growing story of shared community memory.

Maybe your small treasure has a story to tell, too.

The Blackstone Historical Museum is open on Thursdays and Saturdays from 12 PM to 3 PM.

At Small Town Post, we believe in telling stories that connect us to our neighbors, our past, and the small moments that make this town special. This curious $5 bill is more than just a piece of paper—it’s a reminder that even in a quiet New England town, history can resurface in the most unexpected ways. If you’ve uncovered something interesting, have a memory worth preserving, or want to share local news, we’d love to hear from you. And follow Small Town Post on Facebook for the latest local stories.

Because in a small town, every voice adds to the story.